Please note that this version of my blog will no longer be updated. My new site can be viewed at historyofdonegal.com. This version of the site will remain online for a short time.

Donegal Annual 2020 Now Available

The Donegal Annual 2020 is now available. Get your copy in your local bookshop, or visit donegalhistory.com to place an order.

Table of Contents

- Cenél nÉoghain in Patrician Hagiography – Dr. Thomas Charles-Edwards

- Two Ballyshannon Philanthropists and their Legacy – Anthony Begley

- Donegal and the Victoria Cross – Richard Doherty

- Kate McCarry: Letterkenny’s First Woman Urban Councillor – Dr. Angela Byrne

- Viking Impact in the Inishowen Peninsula – Darren McGettigan

- Rev. Edward Glackin 1806-1896: Famine Relief in Glenties – Katelyn Hanna

- Gaelic Surnames and Settlement Patterns in South West Donegal 1659-1857 – Tomás G. Ó Canann

- DNA Analysis: Researching Donegal Ancestry – Dr. Maurice Gleeson and Dr. Sam Hanna

- The Origins of the Uí Dochartaigh of Inishowen – Brian Lacey

- Manor Courts in the Early Nineteenth Centur – Raymond Blair

- Foyle College Donegal Connections – Dr. Robert Montgomery and Seán McMahon

- Convoy Woollen Mills – Belinda Mahaffy

- Changing Features of the Protestant Community In North Donegal from an Occupational Perspective – Edward Rowland

- Andrew Elder (1821-1886), Castlefin: Campaigner For Land Reform – Dr. William Roulston

- William J. Doherty, Buncrana: Engineer, Antiquarian and Politician 1834-1898 – Dr. Seán Beattie

- Patrick Sarsfield Cassidy 1852-1903: From Dunkineely to New York – Helen Meehan

- James Musgrave: Man of Iron – Lulu Chesnutt

- The Pipe Organs of County Donegal – Derek Fleming

- From Malin to Wisconsin: The Friar’s Curse by Michael Quigley – Des Doherty

- Book Reviews/Officers 2020-21

- Donegal Bibliography 2019-2020 – Rory Gallagher

Culdaff Village 100 years ago

Download a PDF of Culdaff Census 1901-1911

I have uploaded the 1901 and 1911 Census for Culdaff village which shows how life in the village has changed over 100 years ago. Many names are still there. Following the very popular Facebook page OUR CULDAFF, set up by Jennifer Doherty, would readers please upload any old photos of family, friends or relations who lived in the village in 1911?

Here is a summary of the occupations in 1911 – 3 shoemakers, I retired navy fireman, post office workers, telegraph messenger, domestics, pubs, stone mason, 2 carpenters, a domestic coachman, 2 boot stores, egg packer, baker, 2 tailors, teacher, clergy, rail goods checker, land surveyor, farmer and some fishermen.

RIC – there was a barracks here from 1827. The RIC men were almost all Catholic, despite the perception that the force was Protestant. They were forced out of the station in 1920 during the War of Independence. The local IRA unit proceeded to wreck the interior afterwards.

While most of the population was Catholic, there were over 40 members of the Church of Ireland (also called Established Church or Irish Church), Presbyterians, Methodists and Episcopalians. The local clergy lived in the village as boarders.

Buildings – apart from grocer shops and pubs, there was a Temperance Hall (Wee Hall), Dispensary (since 1827), National School, Church, and a Loan Fund (since 1843).

Coastguards – not listed, but they had their own accommodation at Meenawara.

In 1911, there was a campaign to extend the railway to Culdaff from Carndonagh. Supporters pointed out that the land was flat and therefore the extension would be inexpensive. A strong case was made that the train would help to develop the export market for fish from Bunagee. James Fleming of Carthage had 6 boats, some of which were built in Killybegs.

- Sean Beattie, May 22nd 2020, in lockdown!

Mass Rock at Tremone Bay – a silent sentinel in the landscape

The hAltoras Mass Rock

Port na hAltora

The Mass Rock at Tremone Bay, Inishowen, is a typical example of a hidden gem of our heritage that the tourist never sees. This was a sacred place for our ancestors: they came here to worship in secret and to bury their dead unbaptised children in the Reiligi on the headland above (reilig – a cemetery). Situated 200 m west of Boat Port, it is encased by a weather-beaten, gaunt arch, which has a close resemblance to the entrance of a Gothic cathedral. The stone steps leading to the site are still visible, worn by the feet of past generations. The priest had his back to the ocean as he celebrated Mass, while a lookout stood on the hillside above to warn of danger. The site is called locally the hAltoras (altóir – altar). It overlooks Port na hAltoras which served as a small port for fishermen but in times of danger offered a safe getaway. To the left is a beautiful natural arch, adorned with wild flowers. Looking seawards from the V of the bend on the Corkscrew Corner, the site is marked by a recently planted fir tree situated on the green pasture above.

In May, there was usually an abundance of seaweed, which in earlier times was harvested as kelp to be used in the manufacture of iodine and also produced acids. It was called the “May Fleeece” and was an important source of income. It was the job of the womenfolk to carry the seaweed in creels to the drying-walls for collection later. Each family in Ballyharry had access to their own strip of the beach, marked out by the rundale system of land ownership. The land strips are clearly visible today, some fenced off, others marked with odd stones. There are no cross markings on the rock, but I did find a memorial card belonging to John Canavan, who died in 2019. The Mass Rock still holds a place in the memory of local people, especially those who lived around Tremone Bay.

The hAltoras was a hidden refuge where Mass was said in penal times dating from the 1700s. Under the Penal Code, priests had to register. Those who refused went on the run, outside the law, with a price on their heads. The site was hidden from public view and also had an escape route seawards, possibly to Inishtrahull island if necessary. The graves of registered priests can be seen opposite McGrorys in Culdaff and in Cloncha churchyard.

Sadly, some of the most infamous priest hunters were native Irish, desperate to obtain their reward.

The present pandemic has succeeded in emptying our places of worship – something which the notorious Penal Laws failed to achieve.

Seán Beattie. Please share if you wish.

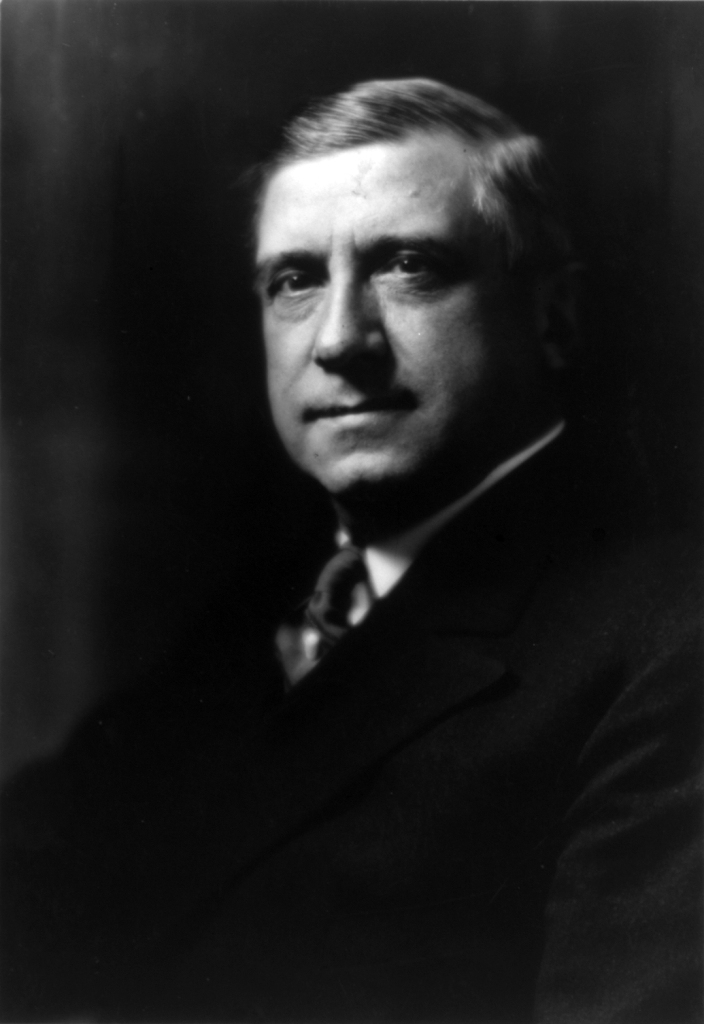

A Malin Head Link to the White House

President William McKinley (1897-1901) had family links to Malin Head

As they look across the great blue waters of the Atlantic, tour guides visiting Malin Head are often heard to remark that the next parish is America. For hundreds of Malin Head folk that comment became a reality, as they boarded the ships of Cooke and McCorkell and the great liners for a new life.

One Malin man who made that journey was David A. Doyle who left Malin Head in his childhood. His family settled in Brooklyn and as an adult he became involved in the religious and commercial life of New York. He was a founder of the Embury Church in Brooklyn. The late 1800s were not a happy place for the Irish in America. On the lowest rung of the social ladder stood the black population, who still remembered the evils of the slave industry. The Irish were just one step above. In general, the native-born Americans welcomed the Irish, especially when they acquired the right to vote and became an influential sector in the electorate by virtue of their numbers. A minority group of fundamentalists, however, known as the Nativists harboured a deep hatred for the Irish whom they regarded as a threat to the American way of life. Their Catholicism was seen as an enemy of their Protestantism; they argued that crime levels were high among the Irish and that if they were involved in politics, they would corrupt the political system because of their numbers. Portraying the Irish as a blight on American society, the Nativists strove to limit the advance of the Irish both politically and economically. It is hard to accept these realities about life just over a century ago.

David Doyle’s achievement was that he overcame these obstacles which his fellow Irish men faced as day labourers and manual workers. It is estimated that within a ten year period after 1900, a quarter of the Irish climbed the social ladder in the worlds of business, transport, crafts, policing, the fire service, trades and office management. Doyle made his name in the world of business in New York. He opened his first trunk and leather store in the heart of the business district of Manhattan and a second in the old Astor House. His merchandising was brash, displaying his goods on the pavements to the annoyance of some politicians. He was a skilled communicator who believed in networking and over the years, he became friends with some of the great celebrities in New York. Among his circle was Abner McKinley, a brother of the President, William McKinley (1897-1901). David Doyle was a cousin of the President. The McKinleys were originally of Scotch-Irish stock who came from Co. Antrim. It is not known if David was ever a guest in the White House, but his family links to the President provided a stepping stone into the higher echelons of American society.

McKinley is remembered today for two reasons. First, he believed in making America great and as a believer in protectionism introduced tariffs on imports to protect US trade, known as the McKinley Tariffs. The tariffs were very unpopular in Ireland where they almost destroyed the cottage industries and the Lace Schools producing home-made goods for the US markets. He is also remembered as one of four US Presidents to die in office, at the hands of an assassin.

David Doyle died on 20 January 1939, leaving a wife, Mary Jane Platt Doyle, three daughters, a son and two brothers, George in Brooklyn and John in Ireland. No plaque bears his name in Manhattan but he may be regarded as an icon for the hundreds of emigrants from Donegal and elsewhere who climbed to the top of the social and economic ladder in the New World.

Seán Beattie, Culdaff, March 2020

Destination Buncrana 1914

Charles M Schwab, one of America’s leading arms dealers, disembarked at Buncrana pier in October 1914 on a top secret mission

On 21 October 1914, the White Star liner Olympic left New York but was directed to lie at anchor in Lough Swilly. The Captain was warned about the dangers of German mines off the mouth of the Swilly and successfully sailed his ship into the Lough. Europe was at war and questions were raised in Buncrana about the purpose of the visit as the ship lay at anchor for four days. There was no communication of any kind with the shore. After a period of four days, two people were observed leaving the ship. It was reported that the passenger was a wealthy American who was accompanied by his valet. Their luggage was left on board. Both were on a top secret mission and the presence of German mines off Lough Swilly presented a serious threat to their safety, hence the delay in Irish waters.

Reporters who tracked the movements of the two men to London later discovered their identities. The well-dressed American was Charles M Schwab. The purpose of Schwab’s departure from the ship was to travel to London to negotiate an arms deal with the Allies. He was the head of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, which was the second largest manufacturer of steel in the US and was a supplier of armour plate and guns to the US government throughout the war.

On 3 November, the Olympic continued on its journey and was noted by Lloyds as it passed Inishtrahull.

Schwab (1862-1939) was descended from German Catholic grand-parents. He was the main figure in the supply of munitions to the US government in World War 1 – another interesting connection between the town of Buncrana and the First World War.

Seán Beattie

St. Patrick in Inishowen

We are unable to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day in our normal fashion in 2020, so here are some of my thoughts from my isolated base in Culdaff

The hagiography (biography of a saint ) of St. Patrick is considered the best guide to the political geography of Ireland in the pre-Viking Age in relation to the location of kingdoms, dynasties and churches. The principal text was written by a bishop called Tírechán, c. 690, quite a while after the saint had passed away. Tírechán was from Connaught, born somewhere along the Moy River which flows through Ballina and is famous for its salmon. According to this source, the saint travelled around Ireland, visiting Connaught and then heading northwards before returning to the midlands. Two other texts add to the history written by Tírechán: the Book of Armagh c. 808 (in particular, the notes), and the Tripartite Life of St Patrick. These three texts provide us with a view of Ireland before the Vikings lashed our coasts.

Patrick entered Donegal through Barnesmore Gap into the Kingdom of Eoghan (often called the Cenél nÉoghain). The tribe of Éoghan would eventually rule supreme following their victory in one of the most decisive battles ever fought in the county, the Battle of Cloíteach in 789.

Patrick travelled northwards through the Fíd Mór (the Great Wood), which was probably in the area of Manorcunningham, now known as the Laggan, overlooking Lough Swilly. At this time, the Inishowen peninsula was divided into three kingdoms. Fergus ruled Domnach Mór Maighe Tóchair, i.e. the area around Carndonagh. Tírechán clearly states that Patrick founded a church at Mag Tóchair (Carndonagh). Not all the inhabitants made him welcome but that is a story for another time.

In the 1600s, the cult of St. Patrick was very powerful in Inishowen. Hundreds made their way across the peninsula to pray at the Carndonagh Cross, one of Ireland’s greatest Patrician shrines in medieval times.

The cross features in Michael Quigley’s epic poem ‘The Friar’s Curse: A Legend of Inishowen, Or, Dreams of Fancy when the Night was Dark’ in 1870. Quigley emigrated from Inishowen after the Great Famine and worked as a labourer, later a carpenter, in America. His 300 page poem references many landmarks and stories from his homeland.

Where Donagh’s granite crosses gray with age,

Stand witnesses of Erin’s faith divine;

Mocking the fierce despoiler’s vandal rage,

Whose wanton fury overturned the shrine?

And broke the stone and blurr’d the sacred line,

The holy legend of the honored dead,

High on the hill above of rude design,

A lofty cairn of stone uprear’d its head,

But for what purpose rais’d tradition nothing said.

‘The Friar’s Curse: A Legend of Inishowen, Or, Dreams of Fancy when the Night was Dark’ – Michael Quigley, Milwaukee, 1870. The book is available from de Burca Rare Books in Dublin.

The Cross is now under threat and experts who recently examined the Cross have noticed dust fragments at the base which suggest deterioration. The Lands of Eoghan group are currently taking up this matter.

For a full account of Patrick’s visit, see the forthcoming issue of The Donegal Annual 2020 in which Professor of Celtic, Thomas Charles-Edwards of Oxford University, an acknowledged world authority on Patrick, will give a very comprehensive account of Patrick in Donegal and his arrival in Inishowen. Subject to conditions, it is now with the printers and will be available in July. To pre-order visit www.donegalhistory.com.

Spelling note – readers often bring spelling oddities to my attention. Please note the form above is pre-twelfth century; changes occurred later. Thanks to Lands of Eoghan, who invited Professor Charles-Edwards here last year, and especially to Max Adams, Colm O’Brien and associates who will return here in 2020 (hopefully) for their tenth visit.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day to all readers, on this unique chapter in our history when we are unable to celebrate our Patron’s Day in the usual fashion (17 March 2020)

– Seán Beattie, Ph. D.

Forgotten Heritage of Carndonagh

- THE WATERLOO PRIEST 1779 in Cockhill, Buncrana. He was one of the most colourful clergymen who served in Inishowen. As a nephew of Bishop Charles O’Donnell, he was marked out for the priesthood. Before he was ordained, he accepted a commission in the British Army and served in the Peninsular Wars. Locals called him the “Waterloo Priest” because he was on the continent at the time of the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. He journeyed through the parish of Clonmany on his horse. A campaigner against tithes (a tax), he found himself in Lifford jail for a short period. With a passion for education, he built five schools in the parish. Two letters written by him have recently come to light in a Carndonagh archive. Writing to the Board of Guardians of Carndonagh workhouse from Straid on 12 May 1847, in a letter marked “Confidential”, he launched a scathing attack on the Relieving Officers. He accused them of misrepresentation in relation to the degree of hunger in Clonmany. This resulted in some of the deserving poor being refused assistance, even though they experienced, in his words, “utter destitution”. In a second letter, he reported on a meeting of the Famine Relief Committee in Ballyliffin in which he highlighted the level of distress in the area. He was a member of the Relief Committee and donated £25 for relief of the poor – a huge sum in those days. Very few of his writings have survived so the signed letters provide a rare insight into the Great Famine in Clonmany parish.

- THE LANIGAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE DIARIES: The Lanigans, drapers, grocers and spirit merchants, ran a prosperous business in the Diamond in Carndonagh. They donated their property to the church and thus an entrance was created at Donagh Café which provided access from the Diamond to the church. The site is marked by a plaque in memory of their philanthropy. James Lanigan kept notes on his activities in the War of Independence and his name is mentioned in Liam Diver’s THE DONEGAL AWAKENING (p 221). His personal accounts, in a private archive, have never been published and contain exclusive information on the history of the War of Independence in Inishowen.

- THE MERCY CIBORIUM: (Ciborium – a vessel for holding Communion). According to folklore from well-informed sources, dating from 1895, this Ciborium came from the friary at Donegal Town which was blown up during the Nine Years War which ended in 1603. The monks fled, taking valuable silver plate along with them, including the Ciborium, as they went into hiding. The Ciborium was on display in the Convent of Mercy, Carndonagh, until it closed down. Today, nothing is known of its whereabouts but it is probably in use in a church. Where?

- THE DONAGH BELL: The monastery in Carndonagh was one of the most celebrated in Donegal, having been founded by St. Patrick. At an Inquisition in Lifford in 1609, there is a reference to the Keeper of the Donagh Bell. The Donagh Bell, as used in services, was donated to the Royal Irish Academy, Dawson St., Dublin in 1853 by John C. Deane, a Relieving Officer at the workhouse. He found it in a pawnbroker’s shop in Carn, probably traded for food during the Great Famine. Later, the Museum of Science and Art, now the National Museum, placed it on exhibition. The last Keeper was Philip McColgan, who died in the 1870s. Record keeping was not as good as it is today and the Donagh Bell can no longer be traced. Where is it now? The Bell of Cloncha monastery is still retained in the parish at Culdaff. Seán Beatt

(A full account of St. Patrick’s journey through Donegal and arrival in Carndonagh will be published in Donegal Annual 2020, due in July 2020, and written by a Professor of History in Oxford University. Details later on donegalhistory.com).

Seán Beattie, Donegal Historical Society, Culdaff. Please share; for reference, cite ww.historyofdonegal.com.

Article on Seán Ó’hEochaidh’s Field Diaries by Lillis Ó Laoire

Dr. Lillis Ó’ Laoire, NUIG

Seán Ó’hEochaidh was one of Ireland’s greatest folklore collectors and he worked for the Irish Folklore Commission in Donegal. Dr. Lillis Ó Laoire, professor in Irish in the School of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, NUIG, has carried out extensive research on his diaries.

In this article, he highlights references to women and how they impacted on Ó hEochaidh’s work. The diaries offer a unique insight into rural life in south Donegal; there are references to local customs and interesting personalities are encountered.

The title of the article is “Tá cuid de na mná blasta/Some Women Are Sweet Talkers”: Representations of Women in Seán Ó hEochaidh’s Field Diaries for the Irish Folklore Commission, and was first published in the Estudios Irlandes Journal of Irish Studies in 2017 (Estudios Irlandeses, Special Issue 12.2, 2017, pp. 122-138).

In the abstract for the article, Ó Laoire states “This article discusses representations of women in diaries written by Seán Ó hEochaidh as part of his work as a field collector for the Irish Folklore Commission (1935-1971). Focusing on a number of well-described events and characters, the article reveals the collector’s attitude to women as they emerge from his writing. It also shows how women could help or hinder his collecting work. The disparities of the lives of a number of working women from Donegal during the period are also highlighted.”

To read the full text of the article, click on the link below:

https://www.estudiosirlandeses.org/2017/10/ta-cuid-de-na-mna-blastasome-women-are-sweet-talkers-representations-of-women-in-sean-o-heochaidhs-field-diaries-for-the-irish-folklore-commission/ (Estudios Irlandeses, Special Issue 12.2, 2017, pp. 122-138; copyright (c) 2017 Lillis Ó Laoire.)

Christmas Rhymers in Inishowen

As a child growing up in Carrowmena, Inishowen, I recall the visits of the rhymers as they went from house to house in the village. They were a noisy, scary lot if you met them on the road in total darkness. To gain entry to each house, they hammered on the door with a walking stick and performed their play in the kitchen. The play ended with a collection. At the end of Christmas, they had a Rhymers’ Ball. I have no idea where they came from.

Glengad Rhymers

The Christmas rhymers in the pictures appeared in the Strand Hotel, Ballyliffin, Co Donegal in December 2002. If I recall correctly, they were touring hotels as part of a fund-raising project and I happened to be in the hotel on a staff Christmas outing. I was in touch earlier with the Folklore Commission who were doing a project on rhymers and some of the folklorists called to Glengad to record the rhymers at work. In the past, Donegal had the largest number of rhymers in the country.

History

In some parts, they are called “mummers” from the French word “mommerie”. Their history goes back to pagan times in Rome, especially the mid-winter feast of Saturnalia. In Shakespeare’s England, they performed “morality” plays. In England, it was St George v. the Dragon but in Ireland it was St. Patrick v. St George. St Patrick always won! In each version, a combatant is wounded and a doctor is called. He is usually a comedian, carrying a brown bag with a bunch of cures. (a kind of Now-Doc!). In medieval versions, Cromwell was the baddie. (Who would it be today?). Rhymers arrived in Ireland following the Plantation but with the advent of television, they disappeared almost overnight.

On the carndonaghheritage.com website, Maura Harkin includes a diary entry by John Norris Thompson in which he recalls the arrival of the Rhymers to Bridge Cottage. A Drumfries Rhymer’s script is also reproduced, transcribed by Kevin Graham. A draft of a Rhymers’ play is also available in a recent issue of the Donegal Annual, which I edit.

Thanks to the Glengad group for the revival of the rhymers in 2002. (All photos by Sean Beattie).